When Cloud Sounds Like Cheaper Hosting

Your company has been selling vertical software for 15 years. You have 50 employees, steady revenue, happy customers ...

21 min read

28.02.2026, By Stephan Schwab

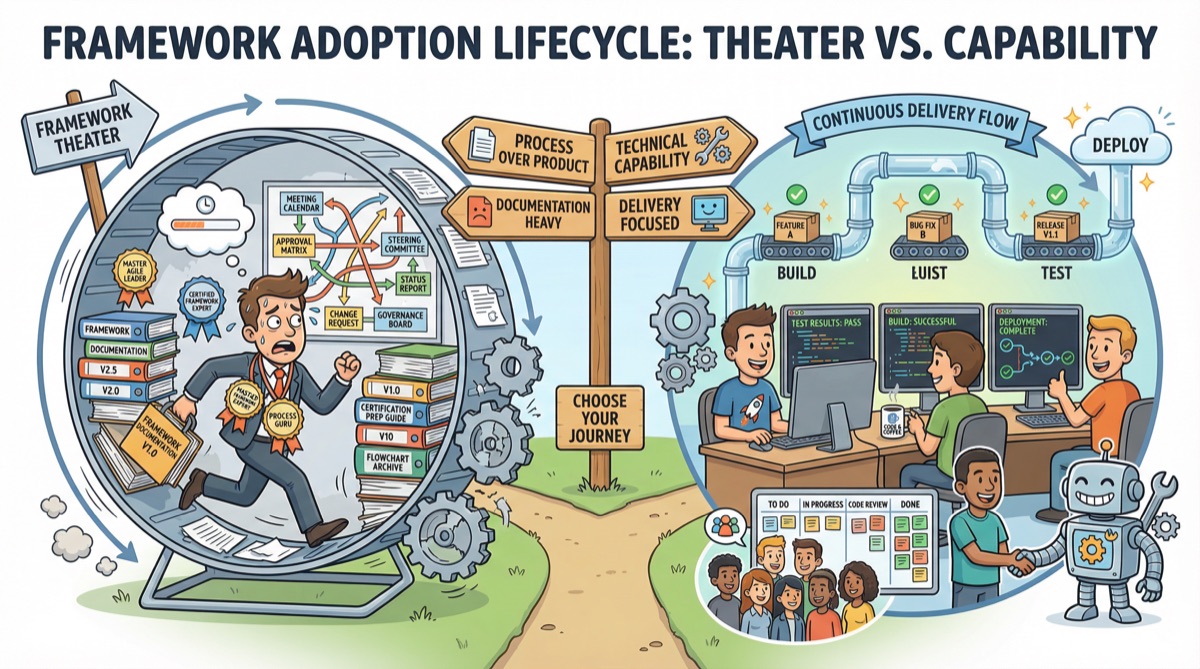

Organizations reach for management frameworks when delivery hurts. But the pain is usually a capability gap, not a process gap. Invest in the people doing the work — help them build genuine engineering discipline — and the framework becomes unnecessary. Here's the cycle that unfolds when organizations reach for process instead, and the exits available at every stage.

Before we map the framework adoption lifecycle, let’s be clear about what actually works: teaching the people who build software how to build it better.

Test-driven development. Continuous integration that actually catches problems. Trunk-based development instead of branch hell. Specifications you can execute. Small batches. Fast feedback. These practices — taught by people who’ve done them, embedded in daily work — fix the problems that make delivery painful. They create the visibility, quality, and predictability that frameworks promise but never deliver.

No vendor sells this because there’s nothing to sell. No certifications to renew. No transformation roadmaps to bill against. No recurring license fees. Just patient work that compounds over time.

The framework lifecycle that follows isn’t inevitable. It’s what happens when someone decides “we need a process” instead of “we need to get better at this.” Understanding the pattern helps you see where you are — and find the exit before you’ve wasted years.

If you’re a non-technical leader reading this, I’m not here to make you feel stupid. You’re not the villain.

You’ve got a board asking why projects slip. Competitors shipping faster. Developers speaking a language you don’t fully understand. When a vendor shows up with case studies and a transformation roadmap — of course you listen. What else are you supposed to do?

Nobody taught you what actually makes software teams work. Business school didn’t cover it. The consultants had certifications to sell. So you reach for what’s available: structure, process, oversight. The problem is that software doesn’t respond to those tools the way other work does. Control in software comes from capability, not from process.

The pattern I’m about to describe isn’t meant to shame you. It’s meant to show you what’s actually happening — so you can make different choices. Every phase has an exit. The exits don’t require you to become technical. They require you to invest differently.

Conferences, speaker dinners, late-night hotel bars. The honest moments when practitioners compare notes. The specific framework changes — waterfall to Scrum, Scrum to SAFe, SAFe supplemented with OKRs — but the stories follow the same beats.

(Waterfall was never meant to be a thing. Winston Royce’s 1970 paper presented it as flawed. The industry read the diagram and skipped the warning. We’ve been doing that with methodologies ever since.)

When hundreds of independent accounts paint the same trajectory, you’re looking at a pattern. Understanding where you are helps you find the exit.

Every framework adoption begins with genuine pain. Projects run late. Quality is inconsistent. Stakeholders feel disconnected from engineering. Nobody knows what will ship or when.

The pain is real. But so is the fear behind the search for solutions.

Put yourself in the VP’s shoes for a moment. The board wants answers. Competitors seem to ship faster. The engineering team speaks a language you don’t fully understand, and they keep asking for things you can’t evaluate — more time, more people, less “interference.” Your career is on the line. You need something you can point to. Something that shows you’re taking action.

When a consultant arrives with case studies, certifications, and a transformation roadmap — that’s a lifeline. It’s defensible. If it doesn’t work, you followed best practices. If it does work, you’re the hero who modernized the organization. The framework isn’t just a solution; it’s career insurance.

The language shifts accordingly. “We lack alignment.” “We need common practices.” “We need to scale what works.” These phrases signal organizational solutions because organizational solutions are what non-technical leaders know how to buy and defend.

Nobody’s being cynical here. The VP genuinely believes this will help. The consultant genuinely believes they’re providing value. The vendor genuinely believes their framework works. Everyone’s acting in good faith — and the trap is already set.

As I explored in Management Frameworks and the Proximity to Snake Oil, the structural incentives favor selling process models over verifiable outcomes.

One more thing: some frameworks actively undermine good technical practices. They’re built on the assumption that software development is manufacturing — predictable, repeatable, controllable through process. Watch what happens when a team wants to pair program instead of attending status meetings. Watch what happens when developers want to refactor before adding features. The framework’s defenders will find reasons why those practices “don’t fit the model.”

If software development is complex — requiring judgment, skill, and constant adaptation — then you can’t scale it through process standardization. You need capability. And capability is harder to sell.

Rollout begins with genuine optimism. New roles appear — look at the box to the right for a sample. That’s not a parody. Those are real job titles from real transformation initiatives, and most organizations adopt a dozen or more of them. Ceremonies fill calendars. People get new titles, new responsibilities, new reasons to feel important.

This matters psychologically. The framework creates winners. The newly certified Scrum Master who was stuck in a dead-end QA role now has a career path. The project manager who feared obsolescence is now a Release Train Engineer. The consultant who spent years learning the methodology finally has paying clients. These people have real stakes in the framework’s success — their mortgages depend on it.

Teams dutifully rename things. User stories replace requirements. Sprints replace milestones. Story points replace time estimates. The vocabulary changes comprehensively.

But beneath the new terminology, the engineering remains largely unchanged. The same code gets written the same way. The same integration pain occurs. The same defects escape to production.

Here’s the tragedy: many people in the room know this. The senior developers see it. Some of the coaches see it. But saying so is career suicide. The framework has executive sponsorship. Millions have been spent. Questioning it publicly means questioning the judgment of people who control your future.

So everyone performs. Activity increases visibly. Outcomes don’t change measurably. And nobody with power wants to hear that.

This gap between ceremony and capability is where management frameworks diverge from what actually fixes software teams. The framework provides structure for coordination — coordination that might not even be needed. Many organizations adopting heavy frameworks are too small to require them. Teams building one-off internal tools or maintaining stable products rarely need cross-team synchronization ceremonies. But the framework doesn’t ask whether coordination is your bottleneck. It assumes coordination is everyone’s bottleneck, because coordination is what it sells. Meanwhile, the framework doesn’t teach test-driven development, doesn’t establish continuous integration discipline, doesn’t refactor legacy architecture, doesn’t build deployment automation.

When results fail to materialize, the pressure flows downhill.

The executive who sponsored the transformation can’t admit it’s not working. Their reputation is attached. So when the board asks why delivery hasn’t improved, the answer has to be “implementation challenges” or “cultural resistance” — not “the framework doesn’t address our actual problems.”

If the framework is correct by definition, any failure must be human failure. Metrics become weapons. Velocity becomes a performance indicator. Sprint commitments become contracts. Dashboards multiply — not for insight, but to identify who’s not complying.

Teams respond rationally. Story points inflate. Definitions of done soften. Green dashboards proliferate while actual delivery capability remains unchanged. Nobody’s lying, exactly. They’re surviving.

More governance appears. Change advisory boards. Architecture review committees. Approval chains. Each layer adds friction while providing the illusion of control. The organization is now reaching for process when it needs sight.

Eventually, reality becomes undeniable. A major release fails publicly. A critical deadline slips catastrophically. A key customer escalates to the board. The comfortable fictions collapse.

This is often the most painful moment for the leaders involved. The executive who championed the transformation faces a brutal choice: admit the approach was wrong, or double down. Admitting failure means losing face — possibly losing their job. It means acknowledging that millions were spent on something that didn’t work. It means the people who warned them were right.

Most people can’t do that. Not because they’re bad people, but because human psychology doesn’t work that way. We protect our self-image. We rationalize. We find external explanations. “The teams weren’t ready.” “We didn’t have enough executive support.” “The culture wasn’t right.” Anything but: “I made a mistake.”

The problems were always there: monoliths requiring coordinated releases, test data that takes weeks to set up, build processes taking days instead of hours. The framework papered over them with activity. Now they’re visible — described as “dependencies,” “QA bottlenecks,” “technical debt.” Safe language that blames systems, not decisions.

This is a decision point. The organization can acknowledge that the real work — engineering capability building — remains undone. Or it can double down on the framework.

Most organizations double down. Because the people making the decision are the ones who’d have to admit they were wrong.

Here’s a face-saving alternative: let a tool tell the story. When Caimito Navigator surfaces that deployment frequency dropped while ceremony overhead doubled, or that the teams ignoring the framework ship three times faster than the compliant ones — the data becomes the messenger. Nobody has to confess personal failure. The evidence simply makes the next step obvious. Leaders who couldn’t admit “I was wrong” can say “the data shows we need to adjust.” Same pivot, preserved dignity.

Doubling down feels logical — and that’s the trap.

The executive thinks: “The framework must work — look at the case studies! Other companies succeeded. The methodology is proven. So the problem must be us. We need more discipline, more coordination, more oversight.”

This reasoning protects everyone’s ego. The vendor wasn’t wrong. The consultants weren’t wrong. The executive who signed off wasn’t wrong. The only thing wrong is execution. And execution can be fixed with more control.

Process layers multiply. A transformation office appears — staffed by people whose jobs depend on the transformation continuing. Centralized planning increases. Approval requirements grow. New middle roles emerge to coordinate the coordination.

Watch what happens to the people who built careers on the framework. The Agile Coaches double down on coaching. The Scrum Masters add more ceremonies. The SAFe consultants propose SAFe extensions. Nobody whose livelihood depends on the framework will ever tell you the framework is the problem.

Teams lose autonomy. Decision cycles lengthen. The organization becomes slower even as it adds more people explicitly tasked with making it faster.

And the best engineers start updating their resumes. They’ve seen this before. They know how it ends. The ones who can leave, do. The ones who stay learn helplessness — a rational response to an irrational environment.

Fatigue sets in across the organization. Eventually, someone suggests that perhaps a different framework would work better. The cycle prepares to restart — and nobody acknowledges that they’re about to repeat the same mistake with a different vendor.

While official processes multiply, something interesting happens in the corners of the organization.

Some teams quietly do what’s necessary to actually ship software. Usually it’s a small group with a trusted manager who provides cover. They set up test automation the framework doesn’t require. They adopt trunk-based development despite official branching policies. They harden their CI pipelines. They slice work smaller than the prescribed story formats. They pair and mob to share knowledge the framework doesn’t transfer.

These teams succeed despite the framework, not because of it. And they pay a psychological price for it.

Their manager lives in constant fear of being “found out.” They have to perform compliance in public while practicing competence in private. They attend the ceremonies, fill in the dashboards, use the vocabulary — and then go back to doing what actually works. It’s exhausting. It builds cynicism. And it creates a quiet resentment toward the people who imposed this theater.

The developers on these teams become cynics too. They learn that leadership doesn’t actually want to know what works. Leadership wants compliance and plausible deniability. The developers protect themselves by never volunteering information, never suggesting improvements, never making waves. They do good work — but only in the shadows.

These teams become the “high performers” that leadership studies and tries to replicate. The replication efforts focus on the visible artifacts — the team structure, the meeting cadence, the tools — while missing the invisible reality: these teams succeed because someone gave them permission to ignore the official nonsense.

Organizations often stabilize in this two-speed state. A few teams deliver reliably. Most teams remain compliance-driven. And the politics get ugly.

The high-performing teams become both heroes and villains. Heroes because they ship. Villains because their success asks an uncomfortable question: if they can do it, why can’t everyone?

Pressure builds to “standardize” — typically by imposing the compliant teams’ practices on the high performers. The stated goal is consistency. The real goal is removing the embarrassing comparison.

This usually destroys the high performance without elevating the struggling teams. Everyone becomes equally mediocre.

The alternative — understanding why the winners win and investing in that capability broadly — requires acknowledging the framework was never the differentiator. Few executives can make that admission.

Some organizations reach a genuine turning point. Leadership recognizes that what matters isn’t the framework but the underlying engineering and product learning capability.

Investment shifts explicitly to practices that actually change outcomes: TDD adoption with real coaching support. Pairing and mobbing as default working modes. CI/CD pipelines that enable multiple deployments per day. Refactoring as a continuous discipline rather than a periodic event. Small batches measured in hours, not weeks. Direct customer feedback loops that bypass the ceremony pipeline.

The framework doesn’t disappear. It becomes optional scaffolding — useful for some coordination purposes, ignored where it adds friction without value.

This phase is recognizable by its symptoms: fewer meetings, more technical work visible, faster integration cycles, fewer defects escaping to production. Teams talk about practices, not processes.

The alternative to genuine capability building is simply starting over with a different framework.

New vocabulary replaces old vocabulary. New consultants replace old consultants. New training replaces old training. New metrics replace old metrics.

The codebase issues remain. The integration pain persists. The testing gaps endure. The architecture constraints continue.

The cycle restarts from Phase 1, often with leadership convinced that “this time is different.” After all, they learned from their mistakes with the previous framework.

What they learned, typically, is to avoid the specific failure modes of the old framework. What they didn’t learn is that the framework was never going to fix what ails them.

A few organizations reach a stable mature state. They’ve learned to select practices based on constraints — flow requirements, quality needs, discovery challenges, architectural realities — rather than framework loyalty.

Governance exists but stays lightweight. Engineering discipline is strong and self-sustaining. Continuous improvement happens through direct feedback and experimentation, not ceremony cycles.

These organizations don’t discuss which framework they follow. They discuss what outcomes they’re pursuing and what practices best serve those outcomes.

They’ve internalized that software development is design work, not a manufacturing process to be optimized through better workflow management.

The lifecycle isn’t destiny. Organizations can exit at multiple points. But exiting requires recognizing where you are.

If you’re in Phase 1: Question the diagnosis. Is this really a process problem? What specific engineering capabilities are missing? What would change if you invested in technical practices instead of organizational structure?

If you’re in Phase 2 or 3: Measure what matters. Not velocity or sprint completion — but cycle time from idea to production, defect escape rate, deployment frequency, and whether customers actually use what you ship.

If you’re in Phase 4: This is the opportunity. The real problems are visible now. Resist the temptation to add more process. Ask instead: what technical capabilities would actually address these constraints?

If you’re in Phase 5A: The double-down is failing. Look for the quiet rebels in 5B. They know what actually works.

If you’re in Phase 6: Study the high performers honestly. Not their ceremonies or tools — their engineering practices. Invest in spreading that capability, not standardizing the dysfunction.

Ask any AI assistant to describe “the typical lifecycle of management framework adoption in software organizations.” The response will mirror what I’ve described here — because this pattern appears so frequently in the training data that any large language model has absorbed it. The cycle is that predictable.

All of this sounds heavy. It is heavy. Careers derailed. Trust destroyed. Good people trapped in bad systems. Years wasted.

But here’s the thing: it also makes for great drama. And drama, sometimes, is easier to absorb than analysis.

Some of us have been turning these patterns into fiction — telenovela-style stories set in software companies. If you’ve made it this far and feel like you need a drink, the stories might be a better choice. They’ll make you laugh. They might make you angry. And somewhere between the romantic tension and the boardroom betrayals, the lessons sink in differently.

La Startup takes place in Bogotá. A fintech company that started with genuine innovation is now drowning in dysfunction. The lead developer has vanished. An Italian Agile consultant is selling snake oil to anyone who’ll listen. Don Hernando, the cattle rancher who bet his legacy on this startup, brings in a German Developer Advocate to find out what’s really happening. The question isn’t whether the company will survive. The question is whether anyone will tell the truth before it’s too late.

Código del Destino is set in Mexico City. LogiMex Systems built an empire on AS/400 legacy systems — for 25 years, their logistics software powered trucking companies across Latin America. Now they must modernize into SaaS or die. The same German Developer Advocate arrives to guide the transformation. But the patriarch’s ambitious nephew has other plans. Enter Bruno Cavalcanti: a Brazilian consultant with a seductive framework and a trail of destroyed companies behind him. There’s forbidden love at an equestrian club, veteran developers terrified of obsolescence, and a family legacy that might not survive the transformation. The framework lifecycle plays out in real time, but you’ll care about the characters first.

Both stories show what the analysis can only describe. The fear in a developer’s eyes when they realize their expertise is being discarded for someone else’s methodology. The quiet moment when a leader finally admits they made a mistake. The cost of silence. The possibility of redemption.

If the pattern in this article feels familiar, the stories might hit differently. Sometimes fiction is just truth with better dialogue.

The lifecycle isn’t a prison. At any phase, organizations can exit by doing something radical: going back to basics.

This means investing in actual engineering capability. Test-driven development. Continuous integration with real automated testing. Trunk-based development. Executable specifications. The practices that high-performing teams have used for decades — the ones that management frameworks don’t even touch.

AI is now an accelerator for this path. Developers who understand fundamentals find AI tools extraordinarily powerful. The AI handles boilerplate and infrastructure glue. This frees developers to focus on what matters: understanding the problem, designing elegant solutions, ensuring quality.

A developer who understands HTTP, HTML, and CSS can use AI to generate exactly the frontend code they need — without the JavaScript framework that brings update hell, supply chain vulnerabilities, and thousands of lines of unknown code. A developer who understands SQL can use AI to write precisely the queries they need — without the ORM that hides what’s actually happening.

The path exists. The tools are better than ever. What’s required is the courage to admit that frameworks were never the answer. The answer was always skill. Craft. Understanding.

I share this pattern not to mock organizations caught in it. The pressures are real. But understanding the lifecycle helps. When you recognize Phase 3 emerging, you can choose differently. When Phase 4 arrives, you can seize the opportunity instead of retreating to Phase 5A.

Framework cycles eventually end. Not because organizations give up, but because they finally build the engineering capability that makes the framework optional.

There’s a cynical joke in our industry: “Organizations are most ready to learn when they have a near-death experience.” Don’t be like them. You don’t have to wait for catastrophe. The exit points are marked. The path is clear. Start walking.

Let's talk about your real situation. Want to accelerate delivery, remove technical blockers, or validate whether an idea deserves more investment? I listen to your context and give 1-2 practical recommendations. No pitch, no obligation. Confidential and direct.

Need help? Practical advice, no pitch.

Let's Work Together