The Product Manager Is Dead. Long Live the Product Developer.

The person who walks into the room with Figma mockups and says 'build this' has run out of runway. AI collapsed the d...

9 min read

24.02.2026, By Stephan Schwab

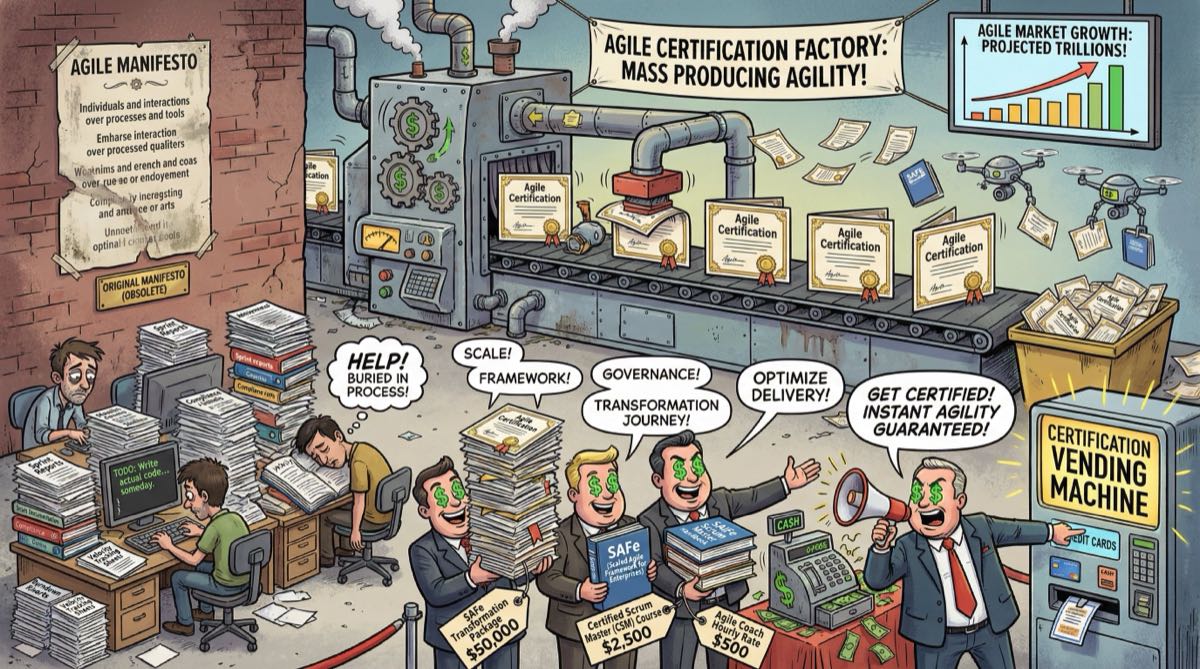

Scrum Alliance reports 1.5 million certificates issued. Scaled Agile has trained over a million professionals across 20,000 enterprises. PMI, the Agile Alliance, and dozens of certification bodies continue to run conferences, sell training, and expand globally. By every organizational metric, the management frameworks for software development are thriving. Yet something significant happened roughly a decade ago. Teams outside the USA can learn from it without repeating the experiment.

In the 1980s and 1990s, most software projects followed “waterfall” — a sequential process borrowed from manufacturing. Analysts gathered requirements for months. Architects designed the complete system. Developers built it. Testers found the defects. Years later, software reached users.

The term “waterfall” comes from Winston Royce’s 1970 paper “Managing the Development of Large Software Systems.” But Royce presented the sequential model as a flawed approach. His paper warned that this method “is risky and invites failure” and advocated for iterative development with feedback loops.

The industry adopted exactly what Royce warned against, then named it after his paper.

In 1985, the U.S. Department of Defense institutionalized this misreading in DOD-STD-2167, requiring “sequential phases of a software development cycle.” It took the DoD nearly a decade to reverse course. In 1994, MIL-STD-498 explicitly encouraged “evolutionary acquisition and iterative and incremental development.”

Iterative development isn’t a recent invention. Gerald Weinberg documented teams using incremental approaches as early as 1957 at IBM. The practices that became “agile” weren’t discoveries — they were recoveries.

The manifesto, published in 2001, captured this insight in four value statements. Scrum provided a rhythm of short iterations. Extreme Programming emphasized technical practices: test-driven development, pair programming, continuous integration. Kanban focused on visualizing work and limiting work-in-progress.

The question is what happened between that original insight and today’s certification industry.

Small teams building software products never needed elaborate process frameworks. A team of five developers working directly with customers, shipping weekly, doesn’t need Scrum ceremonies to stay aligned. They don’t need SAFe’s coordination layers because there’s nothing to coordinate.

The frameworks emerged for large organizations with many teams, complex interdependencies, and layers of management far removed from actual work.

The Chrysler Comprehensive Compensation (C3) project proves disciplined engineering works even inside large corporations. Started in 1993 as a payroll system for 87,000 employees, by 1996 the project had yet to print a single paycheck after three years of traditional development. Kent Beck was brought in and, with Ron Jeffries, introduced the practices that became Extreme Programming.

Within roughly a year of adopting XP, the system went live. It worked. Engineering practices — not a management framework — turned a failing project into a functioning system.

DaimlerChrysler cancelled the project in 2000 after acquiring Chrysler. A manager announced at the XP conference that DaimlerChrysler had “de facto banned XP.”

The practices that rescued the project were discontinued. Not because they failed, but because they didn’t fit the acquiring organization’s management culture.

The “software crisis” was named at the 1968 NATO Software Engineering Conference in Garmisch, Germany. Software projects consistently ran over budget, over schedule, and often failed to work at all. As explored in Bridging the Great Divide, the fundamental misunderstanding between technical and non-technical people dates back to this same moment.

Edsger Dijkstra, in his 1972 Turing Award lecture:

“The major cause of the software crisis is that the machines have become several orders of magnitude more powerful! To put it quite bluntly: as long as there were no machines, programming was no problem at all; when we had a few weak computers, programming became a mild problem, and now we have gigantic computers, programming has become an equally gigantic problem.”

Software development isn’t manufacturing. It’s design work that doesn’t scale the way production lines do. Adding more people often makes projects later, not faster.

Large organizations responded with industrial management techniques: more documentation, more phase gates, more separation between thinking and doing. DOD-STD-2167 and its commercial imitators institutionalized exactly the approach practitioners knew didn’t work.

The ongoing software crisis — never resolved, still producing the same failure rates documented in the 1960s — creates perpetual demand for new process solutions. Each failed methodology creates the market for its successor. (For more on the proximity of management frameworks to snake oil, see the earlier article.)

The irony is that the original Agile Manifesto was written by practitioners explicitly rejecting management-centric approaches. They valued “individuals and interactions over processes and tools.” The opposite of what the certification industry eventually sold.

Dave Thomas, one of the seventeen original Agile Manifesto signatories, in his 2014 article “Agile is Dead (Long Live Agility)”:

“The word ‘agile’ has been subverted to the point where it is effectively meaningless, and what passes for an agile community seems to be largely an arena for consultants and vendors to hawk services and products.”

The public statements of the people who created these approaches:

2009: Ken Schwaber, co-creator of Scrum, leaves the Scrum Alliance after disagreements over “assessments, certification, and a developer program.” He founds Scrum.org the following year.

2013: Schwaber calls SAFe “unSAFe at any speed”:

“The boys from RUP (Rational Unified Process) are back. Building on the profound failure of RUP, they are now pushing the Scaled Agile Framework as a simple, one-size fits all approach to the agile organization.”

2014: Dave Thomas declares “Agile is Dead” and proposes retiring the term entirely.

2018: Martin Fowler, in his Agile Australia keynote:

“Our challenge at the moment isn’t making agile a thing that people want to do, it’s dealing with what I call faux-agile: agile that’s just the name, but none of the practices and values in place.”

And:

“The Agile Industrial Complex imposing methods upon people is an absolute travesty.”

2018: Ron Jeffries publishes “Developers Should Abandon Agile”:

“I would like the world to be safe for developers… it breaks my heart to see the ideas we wrote about in the Agile Manifesto used to make developers’ lives worse, instead of better.”

He recommends developers “detach their thinking from any particular named ‘Agile’ method” and coins “Dark Agile” and “Dark Scrum” to describe imposed, compliance-focused implementations.

These aren’t fringe critics. These are the architects of the original movement.

The original manifesto values:

The certification industry discovered that the right side sells better. Processes can be packaged. Tools can be licensed. Documentation can justify billing. Plans create contracts.

The left side — individuals, interactions, collaboration, responding to change — requires judgment and context. It resists standardization. It doesn’t scale as a product.

The industry built elaborate frameworks around the right side while claiming the mantle of the left.

The framework commercial machine expanded globally with roughly a five to ten year lag. SAFe rollouts in Europe accelerated between 2015 and 2020. The same trajectory American software teams experienced is now repeating internationally.

Teams who haven’t yet committed to a framework purchase can observe what happened without paying for the lesson.

The 17th and 18th State of Agile reports show that 42% of organizations now use hybrid models, mixing agile practices with traditional approaches. Teams discovered that dogmatic adherence to any framework produces worse outcomes than thoughtful adaptation to context.

The frameworks remain useful as diagnostic tools. Scrum’s ceremonies can reveal dysfunction. SAFe’s architectural patterns can expose integration friction. Kanban’s visualization can surface bottlenecks.

The problem emerges when the framework becomes the goal rather than the lens. When “doing Agile” replaces “delivering value.”

The relevant question isn’t “Which framework should we adopt?” but “What specific capability do we need to develop?”

When the manifesto authors describe what actually works, they return to technical practices: test-driven development, continuous integration, refactoring, pair programming, small batch delivery.

These practices don’t require certification. They don’t scale as consulting products. They require disciplined application over time.

Martin Fowler’s 2018 critique identified three challenges:

Notice what’s missing: framework selection, scaling patterns, governance structures. The path forward isn’t more methodology. It’s better engineering.

Engineering practices that produce observable outcomes: shorter lead times, lower defect rates, faster recovery from incidents, genuine user adoption. These metrics don’t care which framework you claim to follow. As discussed in Management Frameworks Don’t Fix Software Teams, frameworks diagnose symptoms while developers remove root causes.

When evaluating any proposed practice or transformation: “What will we be able to observe, in production, that we cannot observe today?”

If the answer involves dashboards, reports, or confidence votes rather than working software in users’ hands, you’re purchasing labels rather than capability.

The frameworks aren’t dead. But the semantic content that once made “Agile” useful has migrated elsewhere: into the quiet practices of teams who ship frequently, respond to evidence, and measure success by what their users actually experience.

For teams outside the USA now navigating these decisions: the ceremony doesn’t produce the outcome. The engineering practice does.

A caution: the same market dynamics that commercialized Agile will likely produce “post-Agile” alternatives targeting developing markets. Different branding, same business model — certifications, transformations, consultant dependencies. The lag between USA adoption and global expansion creates arbitrage opportunities. Skepticism toward the incumbents shouldn’t translate into trust for their critics-turned-competitors.

Before signing contracts with transformation consultants, consider observing what’s actually happening.

Most executives making decisions about software delivery have limited visibility into the work itself. They receive status reports, confidence votes, and velocity charts — none of which reveal whether software is reaching users or whether teams are struggling with integration friction, unclear requirements, or technical debt.

Caimito Navigator synthesizes what your teams are actually doing — from daily logbooks and delivery signals — into weekly insights that any non-technical manager can understand. No framework purchase required. No certification needed. Observed facts about your delivery reality.

The service includes conversations with experienced practitioners who can help interpret patterns and suggest targeted improvements. No buying pressure, no upselling to transformation programs.

Many organizations discover that their teams already know what’s broken. They just need someone to surface that knowledge to decision-makers who can remove obstacles. Sometimes the most valuable intervention isn’t a new process — it’s visibility into the process you already have.

Let's talk about your real situation. Want to accelerate delivery, remove technical blockers, or validate whether an idea deserves more investment? I listen to your context and give 1-2 practical recommendations. No pitch, no obligation. Confidential and direct.

Need help? Practical advice, no pitch.

Let's Work Together