Beyond the Solo Developer Myth: Pair Programming, Mob Programming, and AI Collaboration

Pair programming has been around since the ENIAC days, yet it remains misunderstood and underutilized. This article e...

8 min read

30.03.2026, By Stephan Schwab

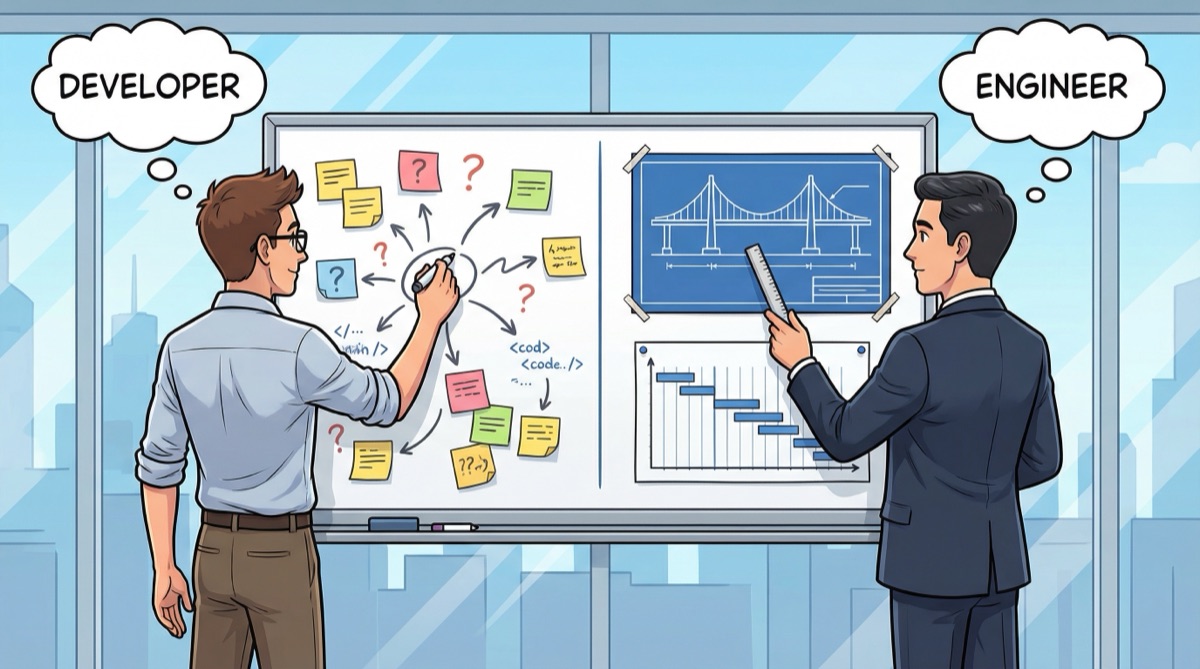

The term "software engineer" was coined as a deliberate provocation at a 1968 NATO conference. Sixty years later, Silicon Valley turned it into a recruiting tool. Engineers apply known standards to known problems. Software developers create novel solutions under uncertainty. The distinction matters because the wrong label feeds the wrong expectations: predictability theater, Gantt charts for creative work, and executives who think shipping software is like pouring concrete. California made "engineer" the default because nobody stopped them. No licensing, no regulation, no accountability for the title. Just prestige inflation.

In 1968, Professor Friedrich Bauer organized a NATO conference in Garmisch, Germany. He picked “Software Engineering” as its title. Brian Randell, one of the attendees, later confirmed the choice was “deliberately provocative.” The software industry was drowning in failed projects, blown budgets, and systems that didn’t work. Calling it “engineering” was a challenge: start acting like engineers. Apply discipline. Follow process. Build things that don’t collapse.

Margaret Hamilton used the same term at NASA during the Apollo program. She meant it literally. Her team was building flight software where bugs killed astronauts. The rigor was real. The testing was exhaustive. The standards were documented and followed. That was actual engineering applied to software.

The problem is what happened next. The aspiration never became reality for the vast majority of the industry. We adopted the title and skipped the discipline. Dijkstra saw this clearly. He watched Data General promote all its programmers to “software engineer” overnight and called the whole field “The Doomed Discipline,” doomed because “it cannot even approach its goal since its goal is self-contradictory.”

He wrote that in 1988. Nothing has changed.

A civil engineer calculates load tolerances using formulas validated over centuries. An electrical engineer designs circuits against known physical constraints. A mechanical engineer specifies materials with documented stress limits. These are professionals who apply known standards to known problems. The physics is settled. The math is proven. The building codes exist because people died until we wrote them down.

When a bridge fails, we investigate. When it fails because the engineer ignored established standards, we revoke licenses. There’s accountability. There’s a body of knowledge with clear boundaries. There’s a professional licensing process with exams, apprenticeships, continuing education, and legal consequences for malpractice.

Software has none of this. The NCEES introduced a Professional Engineer exam for software in 2013. They discontinued it in 2019. Not enough people bothered to sit for it. The ACM and IEEE examined the idea of licensing software professionals and concluded that “the framework of a licensed professional engineer, originally developed for civil engineers, does not match the professional industrial practice of software engineering.”

Read that sentence again. The two largest professional computing organizations in the world said: what we do doesn’t match what engineers do. And then everybody kept using the title anyway.

In parts of Canada, calling yourself an engineer without accreditation is illegal. In several European countries, the title is regulated. In Texas, you can’t legally call yourself an engineer without a PE license (though enforcement for software roles is effectively nonexistent).

California doesn’t care. And that’s where the entire global software industry takes its cultural cues from.

Silicon Valley turned “engineer” into the default title for anyone who writes code. Ian Bogost captured this perfectly in The Atlantic in 2015: “In the Silicon Valley technology scene, it’s common to use the bare term ‘engineer’ to describe technical workers. Somehow, everybody who isn’t in sales, marketing, or design became an engineer.”

Why? Several reasons, none of them related to actual engineering:

Prestige. “Software engineer” sounds better on a business card than “programmer.” As one academic put it: “If you are a programmer, you might put ‘software engineer’ on your business card, never ‘programmer’ though.” Same work. Better branding.

Recruiting. Startups competing for talent in a tight labor market discovered that “engineer” attracts more applicants than “developer.” The title became a hiring tool, not a description of practice.

Compensation structures. Job titles affect salary bands. “Engineer” slots into higher compensation brackets than “developer” or “programmer” in corporate HR systems. The title carries a pay premium that has nothing to do with rigor or discipline.

No one to say stop. Unlike civil or mechanical engineering, there’s no licensing board, no accreditation body, no legal framework that prevents a company from calling every coder an engineer. So they do. Because why wouldn’t you, if the title costs nothing and pays more?

Google’s own book, “Software Engineering at Google,” tried to redefine the term entirely: “software engineering can be thought of as ‘programming integrated over time.’” That’s an interesting frame. It’s also admission that the word “engineering” is being stretched until it means something completely different from what the rest of the engineering profession understands.

This isn’t pedantry. The label shapes expectations. And wrong expectations kill projects.

When you tell a board of directors that you have “sixty software engineers,” they hear “sixty professionals applying known standards to produce predictable results.” They expect Gantt chart accuracy. They expect that more engineers means faster delivery. They expect the kind of linear predictability that works for constructing a warehouse but has never worked for building software.

Software development is sometimes craft and sometimes trade, but it’s rarely engineering in the traditional sense. A tradesperson installs a kitchen following established patterns. A craftsperson designs and builds a custom piece. An engineer calculates stress tolerances for a bridge. A developer? A developer figures out what to build while building it. Requirements change midstream. Users don’t know what they want. The technology shifts under your feet. This is creation under uncertainty, not application of known standards.

The “engineering” label feeds the fantasy that management frameworks can deliver the same predictability for software that they deliver for construction. It’s why companies still plan six-month projects on fixed timelines, why they staff to a plan instead of adapting the plan to reality, and why they’re shocked when the schedule slips. Bridges don’t pivot. Software does. Or it should.

Electricians have authority developers don’t, and part of the reason is that electricians don’t pretend to be something they aren’t. They have a clear scope, regulated competence, and the power to say no backed by code (the building kind). Software developers have borrowed a prestigious title without the infrastructure of accountability that makes it meaningful.

Software development is a creative, iterative discipline performed under radical uncertainty. The requirements are incomplete. The tools evolve continuously. The solution space is unconstrained by physics. Two developers solving the same problem will produce fundamentally different solutions, both of which might work. That never happens with bridge calculations.

This doesn’t make software development lesser than engineering. It makes it different. A different discipline with different constraints requiring different management approaches. Treating it as engineering is not a compliment. It’s a misunderstanding that leads to bad decisions.

Treating developers with respect starts with calling them what they are. Not because “developer” is a prettier word, but because accuracy in language produces accuracy in expectations. When you understand that software development is creative work performed under uncertainty, you stop asking for fixed estimates on novel problems. You stop measuring productivity by lines of code. You stop assuming that adding people makes things go faster.

The best software teams I’ve worked with don’t call themselves engineers. They call themselves developers, or simply the team. They focus on technical practices that actually produce results: test-driven development, continuous integration, trunk-based development, executable specifications. These are disciplines, yes. But they’re disciplines of craft and discovery, not disciplines of applied physics.

Silicon Valley won this naming war decades ago. “Software engineer” is embedded in job postings, compensation structures, visa applications, and LinkedIn profiles worldwide. Nobody is going to rename the industry.

But the thinking underneath the title can change. Executives who understand the difference between engineering and development make better decisions about timelines, budgets, and team structures. They stop expecting factory predictability from creative work. They start investing in technical capability instead of framework adoption.

Call yourself whatever the HR system requires. Put “engineer” on your LinkedIn if it gets you past the recruiter’s keyword filter. But when you sit in a planning meeting and someone asks why the project can’t be planned like a construction project, you’ll know the answer.

Because you’re not an engineer. You’re something else. Something harder to manage, harder to predict, and in many ways, harder to do well. You’re a developer. And that’s not a consolation prize. It’s a more honest description of a more complex reality.

Let's talk about your real situation. Want to accelerate delivery, remove technical blockers, or validate whether an idea deserves more investment? I listen to your context and give 1-2 practical recommendations. No pitch, no obligation. Confidential and direct.

Need help? Practical advice, no pitch.

Let's Work Together